Whose Bible is it anyway?

It is often said that the Orthodox Faith is founded on Scripture (the Old and New Testament) and Tradition, but these two pillars of the Church are not completely separate, they exist within each other and because of each other. The Bible belongs to the Orthodox Church because the Old Testament was fulfilled by Christ Who made us a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a peculiar people (1. Pet. 2:9). In fact, as we shall discuss below, the New Testament in the form we know today only exists because of the Church.

The New Testament, as the book we are familiar with today, did not exist in the first centuries of Christianity. It was only in the period AD 140-200 that the Church began to consider which writings should be accepted as genuine. It was during this period that the four Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were universally accepted, but several other books such as the Epistle of Saint Paul to the Hebrews and the Revelation of Saint John remained deeply controversial for many centuries.

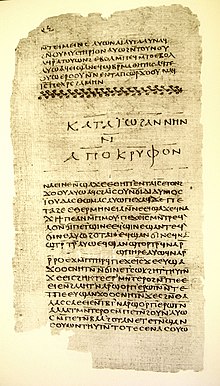

At this time there were a number of other writings circulating that were believed, by many, to be genuine Gospels. The most well known is the so-called Gospel of Thomas (right) a complete version of which was discovered at Nag Hammadi, Egypt in 1945 and dated to around AD 340. Other fragments of this work have been dated in the range AD 40-140. So even as early as seven years after Christ’s Resurrection, writings existed which some regarded as Gospels but which the Church would later go on to reject.

At this time there were a number of other writings circulating that were believed, by many, to be genuine Gospels. The most well known is the so-called Gospel of Thomas (right) a complete version of which was discovered at Nag Hammadi, Egypt in 1945 and dated to around AD 340. Other fragments of this work have been dated in the range AD 40-140. So even as early as seven years after Christ’s Resurrection, writings existed which some regarded as Gospels but which the Church would later go on to reject.

The Gospel of Thomas was highly regarded by the third century Manichean sect, but they couldn’t have possibly written it because it was in existence more than a hundred years before they began. The Gospel of Peter is dated to the middle of the second century. Like the Gospel of Thomas this so-called Gospel was quickly disowned by the Church due to its promotion of Docetism – a term that describes the belief that Christ’s Body was not real.

The content of the New Testament began to take shape between AD 200-400. During the same period the Church was formulating the Creed at the First and Second Ecumenical Councils, setting out clearly in writing the essential aspects of the Christian Faith and correcting the errors promoted by the heretics of the day. The Orthodox Church, therefore, was setting out the boundaries of the Christian Faith and, at the same time, defining the content of the New Testament.

The third century church historian Eusebius lists twenty-seven books as part of the New Testament including St. Paul’s Epistle to the Hebrews and the Revelation of St. John neither of which, at this time, were universally accepted. This list was accepted by the Council of Carthage in AD 391 and therefore, in the Western Church at least, the canon of the New Testament was decided. In the Eastern Church the debate continued until the Church as a whole accepted all the current books of the New Testament including the Book of Revelation at the Quinisext Ecumenical Council in AD 691.

It is clear that the criterion that the Church used to decide which writings to accept, and which to reject, was theological and not historical. The Church is not a museum in which everything old is regarded as being superior to anything new. If it was, then the Gospel of Thomas would have been accepted by the Church simply due to its ancient provenance.

We have discussed on what basis the Church accepted genuine Scripture, but are there any of these original Scriptures still around? The earliest surviving copies of the New Testament were written on papyrus, produced from the fibres of the Egyptian plant of the same name. Fortunately, despite the somewhat brittle nature of papyrus, there are many ancient papyrus fragments from the earliest centuries of Christianity in libraries all over the world.

The Chester Beatty Papyri held at the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, date from the third century. Papyri XII from this collection contains chapters 97-107 of the Book of Enoch and portions of a homily attributed to St. Melito of Sardis. Interestingly, the Orthodox Church does not recognize the Book of Enoch as part of Scripture, but it does acknowledge Melito of Sardis as a saint. He is commemorated on April 1st in the Slavic Orthodox Churches.

A papyrus fragment of the Gospel of Saint Matthew held at Magdalen College Library, Oxford has been dated as early as AD 70 by the eminent papyrologist C.P. Thiede. This would place this genuine Gospel in roughly the same period as the spurious Gospel of Thomas. Papyrus 66 (Bodmer II) is the oldest surviving papyrus codex containing a near complete Gospel of St. John and dates from the second century (a ‘codex’ consists of sheets folded in half and sewn together).

The John Rylands Library at the University of Manchester holds many important papyrus fragments. Rylands 458 dates from the mid second century and contains the Septuagint translation of the Book of Deuteronomy. Rylands 457 contains part of the Gospel of Saint John and is dated between AD 100-120.

Not only do ancient examples of Scripture still exist there are also fragments containing hymns from the Orthodox Church services. For example, part of the text of the hymn ‘Under thy compassion do we flee O Theotokos…’ that is sung at Orthodox Vespers can be seen on the papyrus fragment, Rylands 470 (right). The writing on this fragment dates from the middle of the third century before the Church had even agreed which books made up the New Testament!

Not only do ancient examples of Scripture still exist there are also fragments containing hymns from the Orthodox Church services. For example, part of the text of the hymn ‘Under thy compassion do we flee O Theotokos…’ that is sung at Orthodox Vespers can be seen on the papyrus fragment, Rylands 470 (right). The writing on this fragment dates from the middle of the third century before the Church had even agreed which books made up the New Testament!

Rylands 470 was originally dated somewhat later purely because historians could not believe that the word ‘Theotokos’ was used in the third century. This kind of circular reasoning assumes that Christianity only started sometime in the fourth century when people began to believe that Christ is God and that the Virgin Mary gave birth to Him (the word Theotokos means ‘Mother of God’).

As well as the numerous papyrus fragments from the first centuries of Christianity, there are also complete, or nearly complete, Old and New Testaments still intact today.

The famous fourth century Codex Sinaiticus (below) contains the entire Old and New Testaments together with the Epistle of Barnabas and the writings known as the Shepherd of Hermas. The Codex Vaticanus is of a similar age, and although it is missing some books of the New Testament, contains an almost complete Old Testament in the Septuagint version missing only 1-4 Maccabees and the Prayer of Manasses. The word ‘Septuagint’ is derived from the Latin word for ‘seventy’ because the work was carried out by seventy translators in the third century BC. The Septuagint is more reliable than the Hebrew Old Testament text used by most English-speaking Bible translators.

The Codex Sinaiticus is named after the Monastery of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai. The Codex was ‘borrowed’ from the monastery in the nineteenth century by Constantin von Tischendorf on the pretext of having it copied. He probably never intended to return it. To cover his deceit, von Tischendorf claimed that he found the Codex in a waste-paper basket and so saved it from burning at the hands of the ignorant monks. In fact, the Codex was catalogued in the monastery archives. Baskets were used for storage because that was how documents were stored in the Byzantine era – they were the filing cabinets of the time. The monastery had simply kept this practice from earlier centuries.

In addition, this method of storage had considerable advantages over that practiced in eighteenth and nineteenth century Western Europe where many priceless ancient manuscripts and codices were rebound by libraries and collectors in the fashionable style of the day. Not only were the original bindings destroyed, but the pages were trimmed to a clean edge so that they could be given a gilded finish. Over the years, successive binders reduced the size of these books considerably even to the extent that text was lost from the edges.

Von Tischendorf managed to obtain the Codex Sinaiticus from the monastery by acting under the patronage of the Tsar of Russia to whom he eventually presented it. Fortunately, the Codex Sinaiticus survived the destruction wrought by the Russian Revolution. In 1933, the USSR sold the codex to the British Museum for £100,000 (around £6.4 million today). The money was raised by public appeal.

Both the Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus were written by hand on vellum which is a specially preserved form of calf, goat or sheepskin. Vellum is well known for its longevity; UK Acts of Parliament are still reproduced on vellum because it is recognized to be exceedingly tough and resistant to aging. Vellum, however, is expensive. An average goatskin has a usable area of around 80cm by 50cm and this is only usable if the skin is perfect and free from scars. Imagine the number of goats needed for a book of any size! This is even before we consider the length of time needed to write out each book of the New Testament by hand. All this considered, it is no wonder that very few laypeople owned a complete copy of the New Testament, let alone the whole Bible, until the invention of the printing press in the fifteenth century.

It might be worth considering how the Bible moved from being a rare book that was treasured by Christians to something left in hotel room drawers. Mass production by the printing press is only part of the answer. The other reason is the invention of Protestantism in the sixteenth century.

The Protestant Reformation led by Martin Luther and John Calvin sought to combat the excesses of sixteenth century Roman Catholicism. However, their traditional version of Protestantism is rare today. They did not, for example, reject everything from the previous centuries of Christianity. They did not teach that anyone could interpret the Bible as he or she wished, and they did not reject the interpretations of the Church Fathers.

Far from following the teachings of the founders of Protestantism, many Protestants seem to believe that the Bible fell from the sky sometime in the 1980s (or whenever their particular sect started). Moreover, they believe that their interpretation of the Bible is able to hold Orthodox Christians to account. Of course our weakness of faith and laxness of behaviour fall very far short of what the Gospel requires, and many Protestants put us to shame by the uprightness of their life and their knowledge of Scripture. Nevertheless, without the Church there would be no universally

accepted New Testament, only a collection of writings (some more ancient

than others).

Regardless of our un-Christian behaviour, the Orthodox Church is the Body of Christ (cf. 1 Cor. 12:27). No one can hold the teachings of the Orthodox Church to account using the Bible because the authors and interpreters of Scripture are members of this Body. We also are members of this Body by reason of the fact that we have been baptized into the Orthodox Faith. However, to be truly Orthodox, and a useful member of this Body (cf. 2 Tim. 2:21) we need to follow the example of the Early Christians by studying the Scripture according to the mind of the Church, strengthening our faith, changing our life by repentance and partaking of the Mysteries of the Church.

Comments

Post a Comment